In his 1978 Inside Story, the eminent Daily Express journalist Chapman Pincher told the story of ‘case-records’ that in 1961 MI5 wanted him ‘to print a series of case-records simply to show what the Russians did and how they did it. This would serve to warn the visitors to Moscow’, whether diplomats or businessmen. Russian agents would seek to suborn Britons, blackmailing them sexually or otherwise into providing information to the Soviets.

Pincher duly printed some of the (anonymised) cases, later issued by MI5 as a booklet called ‘Their Trade is Treachery’. Pincher recalled:

Written almost like a paperback thriller [Pincher also wrote spy novels], it is a manual intended for perusal by officials with access to secret information and is not available to the public. Its contents, describing the often brutal methods used by the KGB [the Soviet secret police] to trap the unwary into serving as spies and saboteurs, would be a valuable warning to any citizen. However, such was the Whitehall objection to any publication of its contents – including those I had already printed – that after mention of the Official Secrets Act produced no result the Daily Express was threatened with an action for breach of Crown copyright if we reproduced any of the contents verbatim. Such are the extremes to which the secret departments will go to preserve their own peculiar brand of power.

A file at the National Archives, INF 12/1341, tells the story of that booklet. In May 1962, MI5 wrote to JM McMillan of the Central Office of Information (COI), UK government’s marketing agency. McMillan quoted the recent Radcliffe Committee on security procedures in the public service, that ‘the biggest single risk to security at the present time is probably the general lack of conviction that any substantial threat exists’. Hence MI5 wanted publicity for its collected cases, to ‘convey an impression of reality and must therefore look different from material associated with the world of fiction’.

Some inside COI were on MI5’s side; Douglas Liversidge of COI wrote to McMillan that he wanted to ‘shake people out of their apathy towards national security’. COI proposed a filing cabinet as a symbol, to convey the security message ‘in a flash’, like another government campaign, the ‘black widow’ to publicise deaths on the roads. MI5’s draft booklet covered how Soviet intelligence worked; its ‘talent spotting’; and how security was a concern for everybody, and that there was ‘no scope for complacency’. The booklet gave an example of a ‘social approach’ to an electronics engineer, who met a diplomat at a trade reception; then was invited to a concert at the Royal Festival Hall. When the engineer moved job, and split from his wife, and needed money, the Russian offered to help – in return for information. To the Russian ‘diplomat’, every contact had potential for exploiting, for spying. With money there came obligation. The booklet acknowledged the Soviets’ skill; that they would find what might motivate the exploited person, whether idealism for Communism, or money, or applied pressure and threat of compromising the person’s standing with employer or wife.

The booklet recalled recent history; that in 1948 – when the Soviet coup in Czechoslovakia heralded the Cold War – the British government had barred communists (and fascists) from government work. That meant communist parties were not a recruiting base for the Russians (and their allies).

The booklet gave examples of what happened instead: to a RAF national serviceman; an MP’s secretary; someone on an exchange visit to Moscow, who got drunk and was subjected to a ‘homosexual assault’ and photographed, then blackmailed. In that case, MI5 wrote, ‘the only sensible course …. Was to make a full statement at the British embassy …. The simple principle of never taking sweets from a stranger’.

MI5 did name some of those in the public domain who did ‘great damage’ to national security – May; Fuchs; Pontecoruo; the spies Burgess and Maclean; Brian Linney; Gordon Lonsdale and his British accomplices; and George Blake. How many others were never caught? MI5 asked: “This last question should be the most sobering thought of all.” Not only did that admit MI5 was less than perfect, it was stating the crux for any security – given that criminals, spies and others doing wrong were hardly going to admit it, how to make a judgement based on unknowns?

The booklet then drew the lessons for all who worked in government: that they should appreciate rules and procedures; and ‘the fact that national security is YOUR concern’. For employers, personnel security made sure ‘that we don’t employ the wrong people in a position of trust and afford access to secrets’.

Next, MI5 listed document security, ‘to provide control of the circulation of secrets papers, so that they re seen only by those people who are intended to see them’. Then came physical security, ‘to enforce adequate standards in the way of cupboards, safes, locks etc where secret documents are kept’. Last but not least, ‘unauthorised people must be kept at a distance by such simple yet essential methods as passes’. The booklet attributed the ‘great majority’ of security failures ‘to the human element – weakness, negligence, or error of judgement’. In favour of the spy, MI5 added, was ‘our way of life. On the whole it is fairly liberal.’

Anyone with access to secret information may be subject to attack, and few people are without weakness, MI5 admitted – which the Soviet bloc intelligence services sought to uncover and exploit. MI5 also admitted that the handbook of security in government departments was ‘uninspiring’, and questioned if senior people were out of date in their basic thinking on security; ‘certainly there is no escaping the fact that in some places security has been definitely bad’. Some were beyond reach of security education, until something startling shocked them out of their complacency.

The booklet gave ‘essential dos and don’ts’ in the office. Such as: keep tidy; don’t take classified papers to the canteen; lock up all classified material at the end of the day; don’t leave keys, even for a few seconds, because a wax impression could be taken; don’t take any classified papers away from the office; don’t hesitate to ask the advice of a local security officer, for example if you came into contact with a Soviet bloc official.

MI5 in December 1963 proposed using photographs of actual spy equipment, such as a torch with hollow batteries, as used by Lonsdale and (Peter) Kroger as found in a house search of 45 Ganley Drive, Ruislip, London. Another MI5 memo of that month stated that their audience for the booklet was ‘largely of lower and middle grade civil servants and members of the armed forces’. It had been first mooted in May 1961 (significantly, around the time of the approach to Chapman Pincher). MI5 had made their first draft by November 1961. A re-draft by COI was presented to the security services in October 1962, but was ‘not considered to meet the purpose’. An officer of the security services, who was a ‘successful author in his spare time’ re-wrote it by January 1963, and this latest version was, according to the file, discussed in great detail within the security services. As this story suggests, everyone felt they were a writing expert; too many cooks were spoiling the broth; and nothing was made final for years, even the title. First it was ‘No snow on their boots’, then ‘Their trade is treachery’.

The booklet would be classified ‘restricted’ and 100,000 copies printed, at a cost of £3500 (hundreds of thousands of pounds in 21st century money). As MI5 admitted, ‘it must be assumed that contents will become public knowledge’. There lay a further delay. MI5 feared adverse publicity, and criticism from Fleet Street (if the title were ‘No snow on their boots’, it would need explaining). As for photographs, MI5 proposed (like a UK atomic energy authority, UKAEA, pamphlet on threats to security) including pictures of the recent ‘Portland spies’ and their equipment. As an aside, in 1963 some 700 government officials attended security services courses.

A film under production by COI on the same lines was largely written by the security services, for screening to government officials on ‘the security lessons of a hypothetical but realistic espionage case’. In January 1964, MI5 was making final requests for amendments, after the Foreign office made comments. That other departments had to give the booklet their blessing only stretched the project further. MI5 cleared the dummy version of the booklet in February 1964, choosing between possible front covers. MI5 proposed that officially, COI (not MI5) would be the stated publisher. According to the local MI5 adviser, the booklet came under the Official Secrets Act, and thus MI5 would not seek press publicity (arguably a peculiar decision, if security was everyone’s concern).

Perhaps inevitably because the project had taken nigh on three years, MI5’s director general was now anxious for production ‘with all speed’. It would have 76 pages and look like a Penguin paperback, and would come out at the same time as a security educational film.

MI5 wrote to Liversidge at COI on February 28, 1964 giving the MI5 local officer’s opinion that if the press published any of the booklet, technically it would be an offence under the Official Secrets Act. The Crown if prosecuting would have to prove that the reporter received a booklet from a Crown employee (‘this in practice can seldom be done’). But, it would be a copyright offence. Still other departments were raising doubts. The Treasury solicitor in March 1964 asked for the true names in the text to be made distinct from the fictitious ones; and pointed out that Pontecoruo was not convicted of anything, although he defected to Russia.

Their trade is treachery was marked ‘for official use’ and on the opening page quoted the then prime minister Harold Macmillan from November 14, 1962; ‘hostile intrigue and espionage are being relentlessly maintained on a large scale’. MI5 described a page of security defences as ‘common sense to make spying more difficult and more dangerous …. Physical security, tiresome at first, can become a habit which once acquired becomes as much a part of daily routine as cleaning the bath’.

The conclusion (on page 59) listed three things: integrity, common sense and knowledge. While the booklet, then, gave some basics, MI5 nor anyone else could enforce (or even measure) integrity or common sense. Where the most copies of ‘Their trade is treachery’ shows where MI5 saw the risks in government: 5500 to UKAEA, 1000 to the Home Office security officer; 2000 to the Post Office’s security section, at room 418, Armour House, St Martins le Grand in central London. As of April 1964, an estimated 23,000 would go to the Army, 900 to the security services, and 1000 to the Foreign Office.

The film warning about espionage, meanwhile, took nearly a year to produce. Black and white, 55 minutes, and costing £22,000 and titled ‘Persona non grata’, it was not for public viewing and was available through COI for security training to government staff that had access to classified information; in particular those who had been positively vetted. It shows a Soviet spy-master assisting with a left-wing journalist, a civil servant and a sergeant in the air force; until, that is, the Soviet man is uncovered, and deported, as ‘persona non grata’.

An April 1964 draft press hand-out described the 10,000-word booklet, so vague in detail as to be misleading (saying only that government was printing ‘thousands of copies …. part of security training and education’).

The file shows the official dilemma between wanting to spread its warning message, and keeping secrets. In December 1964, an MD of a Lancashire firm wrote to COI, asking for ‘Their trade is treachery’, because staff regularly visited the Soviet Union; but COI would not send any. Bill Deedes, the minister without portfolio in the Conservative government (and before and after a broadsheet journalist) asked for a copy; and passed it to the chief whip; who wanted to hold on to it. On July 31, 1964, Deedes’ private secretary Derek Taylor Thompson wrote to COI, asking for another. MPs could only see a copy on a ‘basis of confidence’.

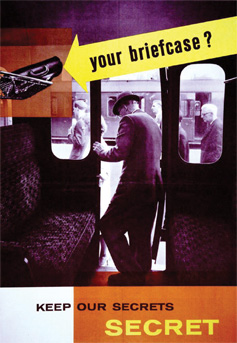

An official 1960s poster from another file at the National Archives, INF 13/203.