We continue an occasional series on security in history, based on freely downloadable files from the National Archives in London. File KV2-412 is among the files created at the end of the Second World War in Europe, as the Allied security services sought to interrogate newly-captured Nazis, to find out among other things what made the Third Reich tick.

The file went into the SS agencies the RSHA (Reich Main Security Office) and the SD (Sicherheitsdienst), the SS’ intelligence service. Its findings undermined the belief – that the Nazis sought to spread, to aid their war effort – that the Nazis were united and efficient. Hitler was ignorant of and disdainful of intelligence reports, the file concluded. Amt VI (office six) of the RSHA carried out political and counter espionage abroad.

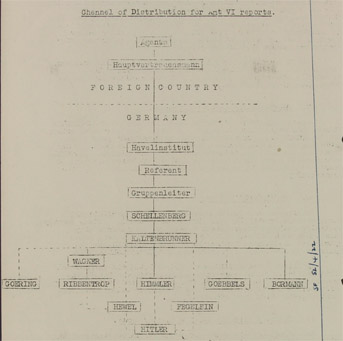

The value of any type of intelligence gathered at any era is not only in its intrinsic worth, but the promptness that it reaches those who may make use of it (pictured). The file as a result of interrogations of the Nazi top echelon in 1945 found that thanks to radio communication with agents, the Amt VI had speedy transmission of news items guaranteed. Flash messages could be sent to the RSHA leaders by teletype: “Thus Himmler [the head of the SS] usually was the first man in Germany to obtain a complete picture of important developments. His information preceded Ribbentrop’s [the foreign minister] usually by a matter of hours. Himmler used this time lag to his own advantage. Usually he simply handed such sensational news to Hitler in a pointed manner, but without any further remarks.”

As that implies, the man who could update Hitler first could look good; and Himmler and Ribbentrop were competing for power. Among others so was Goering as head of the air force; Goebbels as minister for propaganda; and the military, to name only three.

The RSHA had lots of arms at work: technical, making weapons (such as bombs, ‘a miniature pistol for assassinations, 20 rounds, calibre 6.35mm’), false documents such as passports (‘developed to a fine art. Upon several occasions agents with counterfeit passports were sent out to foreign police and consular agencies, with the only purpose of testing the quality of their false papers. Not once was suspicion aroused.’), and signal interception. As for actual gathering of intelligence, the interrogators concluded that in Britain, Ireland and the United States it was ‘non-existent’.

The file tackles the basic job of an intelligence service; to gather factual material for the better making of public policy. But did Nazism, or any one-party state, want to hear things that didn’t fit the ideology?

As a report on the RSHA noted, the office surveyed all German life on the home front for the Nazi regime to learn of internal problems, from juvenile delinquency and corruption by Nazis to popular opinion and what people in ‘high society’ were saying. However: “Where all decisions are made at the top, a constructive intelligence service is self-destructive and only the repressive aspects of such an agency can be permitted to subsist.” In other words, the Nazi leaders preferred their illusions and prejudices to hear about bad things; let alone criticism of themselves.

If RSHA staff making reports found that their reports got toned down, some resigned themselves to that, and changed what they wrote – saving ‘their superiors the trouble of having to do so later on’. Or; others reacted the opposite, choosing to ‘paint things blacker than they really were’, assuming that once reports were toned down, ‘enough of the truth would remain’.

RSHA reports had to go through the head of the SS, Heinrich Himnmler. “But Himmler was not the man to risk an open break with anybody who still had some vestige of power. Therefore no reports against leading personalities ever penetrated beyond Himmler, unless it was for his own purposes.” In any case, the file judged, most in the Nazi security service ‘were fanatics without the detachment and background necessary for the efficient conduct of an intelligence service’.

Amt IV was the secret police, the Gestapo, ‘by far the most dreaded section’; contrary to popular belief, not particularly efficient, according to the file.

As for foreign intelligence by Amt VI, before the war, it tended to use the same bodies to plant agents abroad posing as business men – the airline Lufthansa, the railways (Reichsbahn) or a steamship line. As a sign of how farflung the agents were, the file described how they went into the Caucasus in southern Russia; and Iran; and Turkey (two SS men ‘camouflaged as members of the German diplomatic missions’).