The bank strongroom once had a fascination in popular culture, and for good reason, writes Mark Rowe.

You can chart the difference between the physical and new, cyber world in films. The 2023 summer Mission Impossible film Dead Reckoning (part one) had drama around whether the heroes would download a cyber payment, while (oddly) on a Continental train. Contrast that with 1960s films such as The Italian Job; and Goldfinger, when James Bond thwarted an attack on Fort Knox in the United States. The vault, holding cash or other valuables, drew thieves, and if the security was so sophisticated (for the time) that the thefts had to be daring, that only added to the appeal for film-makers and story-tellers generally.

A considerable cash economy still exists after the covid pandemic made contactless and electronic payment more hygienic, and cash in transit vans and betting shops and convenience stores still require protection for sometimes lone workers against thieves, who are, security managers and retailers alike warn, are both increasingly violent and readier to resort to violence. Yet the large and audacious theft from a bank vault, cash handling centre or safe deposit room, has become unusual, even a period piece. Criminals have made a rational choice: why go to the time and trouble to overcome physical security (and the unpredictability of it all; police may turn up before you flee with the stolen goods, and witnesses, bystanders and staff may have a go at you) when you can commit any kind of online fraud, and the chances of police collaring you are vanishingly small?

As for how much money a bank might hold, consider that in the 1940s (say) Britain ran on cash. A factory needed cash to pay its workers, weekly; that required a routine of white-collar staff attending a bank, collecting cash, taking it back to the factory, sorting it into the correct pay packets, and handing it over. Thieves could note the routine and pounce accordingly, whether those handling the cash were at their most vulnerable in transit, or the cash was easiest to steal if left overnight. Useful records date from the middle years of the Second World War, when Britain made contingency plans in case of German invasion (although when invasion was likeliest, in the summer of 1940, Britain had no time to plan). A county town’s bank might hold £100,000 in cash. If the Nazis invaded, would the cash economy be suspended, until the invaders were ousted, or would workers and businesses still need to be paid and deposit cash? Would cash have to be evacuated before the Nazis occupied a place? To give a sense of how much money £100k was in, say, 1943, a workman might earn £250 a year.

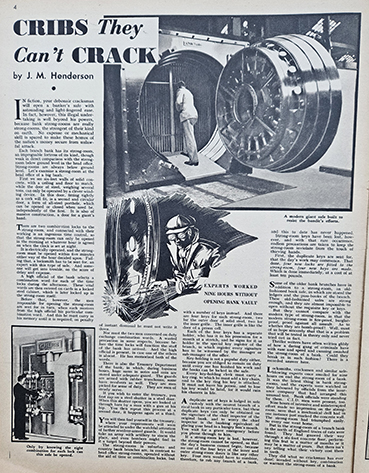

An article (pictured) in the July 15, 1939 weekly edition of Modern Wonder magazine aimed at teenage boys, hailed the bank strongroom as ‘the strongest of their kind on earth. No expense or mechanical skill is spared to make these homes of the nation’s money secure from unlawful attack.’

The article differentiated the strong-room in each branch from the strong-room in the head office of a big bank. The era was between what we now call OT (operational technology, of physically-worked gears, pulleys and levers) and the electronic and now internet networked systems of our day. Electricity powered ‘an ingenious time control’ so that the combination locks to the strong-room could only open at a set hour; and had to be opened within five minutes of the agreed time (‘failing that, a locksmith has to be sent for’). That shows besides the set hours of a bank – no 24-hour banking in 1939!

The year 1939 was a pre-computer age, to state the obvious, as this procedure shows:

‘A high official of the bank selects a combination word for each of the time locks during the afternoon. These vital words are then entered on cards in a locked steel cabinet, which is later locked up in the strong-room itself.

‘Before that, however, the men responsible for opening the strong-room are sent for in turn, when each receives from the high official his particular combination word. And this he must carry in his memory until it is required; on penalty of instant dismissal he must not write it down.’

The ‘modern’ strong-room was fire-proof, burglar-proof and assault-proof. The article records what we would term a ‘penetration test’:

‘Locksmiths, cracksmen and similar safe-blowing experts once assailed for nine hours on end the strong-room of a bank. It was the latest thing in bank strong-rooms, and the experts were watched as they laboured by officials from the insurance company that had arranged this unusual test. Bank officials were standing by them. CID men were also present.’

Nine hours of attack made no impression. The article also ranged over the organisational precautions (each key-holding clerk had to attach the key to his person by a chain; duplicate keys were lodged with another bank’s branch; if a key did get lost, the duplicate keys would open the strong-room and then new locks would be fitted – at a cost of £10!).

In the ‘Treasury Department’ of the big bank that had ‘huge’ sums of banknotes and coin coming in and out in business hours, ‘the guards are armed with rubber truncheons; some have revolvers as well. They are men picked for sense of duty. They are men of steady nerve.’

The paradox is that between then and, let’s say, the beginning of SIA-badging in the mid-2000s, private security took on ever more, more responsible and more public, police-like duties, coming out of the literal basement of a strong-room to patrolling shopping malls, hospitals and campuses; yet even though crime was generally ever-increasing, those security officers had those weapons – even though for self-defence – taken away.